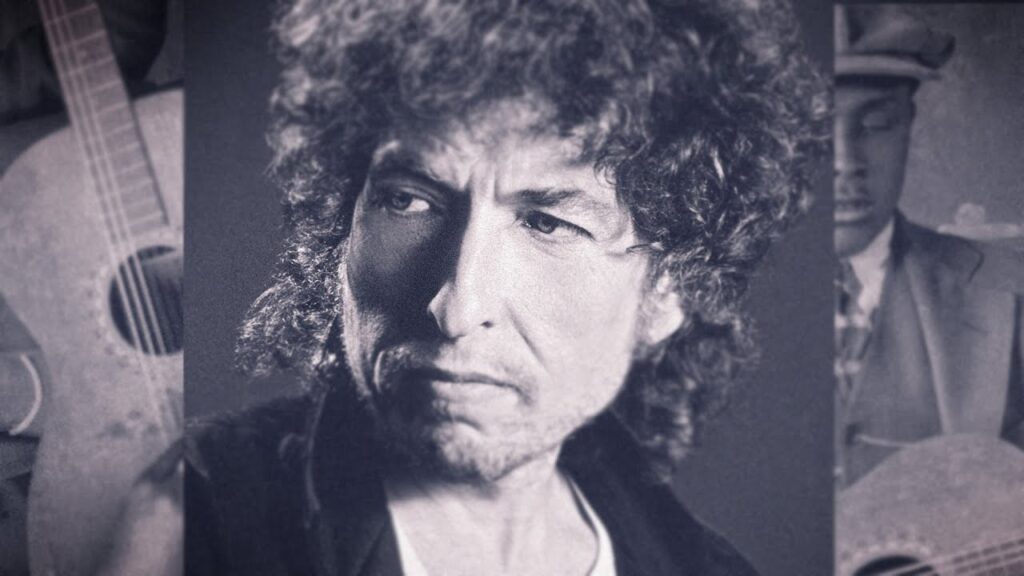

Most Dylanologists disagree about which is the single niceest tune in Bob Dylan’s catalog, however few would deny “Blind Willie McTell” a spot excessive within the running. It might come as a surprise — or, to these with a certain concept of Dylan and his fan base, the precise oppowebsite of a surprise — to be taught that that tune is an outtake, fileed however never fairly completed within the studio and availin a position for years solely in bootleg kind. “Blind Willie McTell” was a product of the sessions for what would grow to be Infidels. Launched in 1983, that album was acquired as somefactor of a return to kind after the Christian-themed trilogy of Sluggish Prepare Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love that Dylan put out after being born once more.

Of the material officially included on Infidels, the niceest impression was probably made by the album’s opener “Jokerman,” at the least in the punk rendition Dylan perfashioned on Late Night time with David Letterman. Not that each Dylanologist is a fan of that tune: within the Daily Maverick, Drew Forrelaxation calls it “random and incoherent,” drawing an unfavorin a position comparison with “Blind Willie McTell,” which is “certain to be remembered as certainly one of Dylan’s most perfect creations.”

The sources of that perfection are many, as defined by Noah Lefevre in the brand new, close toly 50-minute lengthy Polyphonic video above on this “unreleased masterpiece,” whose origin and afterlife underneathrating how thoroughly Dylan inhabits the musical traditions from which he attracts.

Like most main Dylan songs, “Blind Willie McTell” exists in several versions, however the one most listeners know (officially launched in 1991, eight years after its fileing) features Mark Knopfler on twelve-string guitar and Dylan himself on piano. Melodically based mostly on the jazz standard “St. James Infirmary Blues” and named after an actual, professionallific musician from Georgia, its sparse music and lyrics manage to evoke a panoramic view encommoveing the blues, the Bible, the methods of the previous South, and certainly, the very history of American music and slavery. Although Dylan himself considered the tune unfinished, he got here round to see its value after hearing The Band work it into their present, and has by now perfashioned it stay himself greater than 200 instances — none, in adherence to the professionaltean character of blues, people, and jazz, fairly the identical because the final.

Related content:

A Massive 55-Hour Chronological Playlist of Bob Dylan Songs: Stream 763 Tracks

“Tangled Up in Blue”: Deciphering a Bob Dylan Masterpiece

How Bob Dylan Saved Reinventing His Musicwriting Course of, Breathing New Life Into His Music

How Bob Dylan Created a Musical & Literary World All His Personal: 4 Video Essays

Primarily based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His tasks embody the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the guide The Statemuch less Metropolis: a Stroll via Twenty first-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social internetwork formerly often known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.